I stopped by race package pickup for North Sun Ultra at The Tech Shop on Friday evening after work. It was my first time running the race and I was pretty stoked to take a shot at it. North Sun is one of the few other locally operated trail races in Edmonton, so it feels like a sister race to Run On. I am also pretty fond of one of the race directors, Laura, after our serendipitous meeting on the trail in BC during Diez Vista 50k a couple years ago. As I picked up my bib and timing chip, I asked Hadley, (another RD on the NSU team) how the trails were looking after the off and on showers throughout the day. As if on cue, Conor, (Laura’s partner), bursts through the door, fresh off the trails, and gave the thumbs up that everything was flagged and ready for us to race.

I had barely driven back to the south side when the skies opened up and it poured. And I mean torrential. It had been a dry spring so the trails can soak up a fair bit of water before they are saturated, but this last storm was pretty intense. I thought about Hadley saying trails were good to go, and went to sleep, curious about whether or not that assessment would change.

I woke up at 5 am to some texts from friends, and an email from the race saying that the start was delayed for an hour, so they could reroute a few sections after all the rain. I was relieved to hear that they were going to protect the trails from the damage that happens when you use them when they’re wet. The importance of protecting our trails in Edmonton is something I learned early on in my trail running days. Thanks to a pretty vocal mountain bike community, the message has always been loud and clear: “Stay off wet trails.”If you are leaving a footprint or rut of any kind, the trails aren’t ready for you. Unlike trails in the mountains, our river valley trails are clay-based so the water doesn’t absorb quite the same, leaving them susceptible to drainage issues and of course footprints or ruts. This isn’t as much of a problem on the maintained paths in the city because they usually have gravel or woodchips put down. However, the single track trail system is a whole different beast. And a pretty contentious beast at that.

The mountain bike community has been working (at times fighting) with conservation groups and city developers to develop an organized and comprehensive trail plan to develop a world class trail network, as well as preserve our incredible precious Edmonton river valley. The Ribbon of Green initiative has been in the works for decades, trying to come up with a solution to develop a river valley trail system that provides something for all trail users, protects wildlife and vegetation, however it’s been a slow process with lots of diverse voices.

The Edmonton Mountain Bike Association has taken a lead on building and maintaining trails, as has approval from the city to do so in certain areas. However, there are still a lot of areas that are either not sanctioned for work by EMBA, or are in what are called ‘Preservation Areas’, sort of a grey area for trail users. And to further complicate things, trail runners don’t necessarily want the same thing from a trail that mountain bikers do. I’m fine with logs down, roots and narrow, overgrown paths. Whereas mountain bikers prioritize wider trails, berms and good sightlines. As the race director for Run On, a race that primarily uses single track trails, many in ‘Preservation Areas’, I have a huge vested interest in the conversation about trail use and protection, and am committed to ensuring our event does not negatively impact the trail system. Each year we clean, clear and reroute the course if needed, and always have a rain out route option ready to go in case the trails are too wet. Thankfully we have never had to use it.

Back to North Sun. All of the 50K racers huddled under the shelter at Emily Murphy Park and listened to Conor announce they had rerouted delicate sections on both the east and west sections of the course, and that they were confident we were good to go. I was a bit skeptical, given that it had rained for most of the night, and continued to do so as they counted down for us to start. We all took off like a stampede towards the east trail network, jostling for position before we were funneled into the first section of single track. Already, we were at a standstill at times as people struggled to gain footing on the slick hills, some people running along the grass on the side of the trail to find better footing or to pass those who were struggling. I immediately felt panicky. All those footprints we were leaving. These trails are not ok and we had no business being on them.

I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on what happened next. Why so many of us continued on despite knowing the damage we were doing, why the race directors took so long to make decisions to reroute, why volunteers felt paralyzed to think for themselves or heed what racers were saying. Why we were all complicit in something so harmful to something we love so much.

The best explanation I can come up with is something akin to the sunk cost fallacy. Basically the inability to end something because you already feel you’ve put a lot into it and it feels too late to pivot or make a change in response to changed circumstances. I rationalized that the race directors wouldn’t send us on trails that we shouldn’t be on, even though the evidence was so obvious, and literally right under my feet; stuck on my shoes in fact. I rationalized that I am not the type to DNF; since I had started the race I had to finish. I even convinced myself that since my race season has unravelled due to the cancellation of the 100 miler I had planned, that I was entitled to finish one of the few races I had left on the calendar. Not to mention that I was told by some volunteers that I had a shot at the podium. (I didn’t, I finished 5th)

When we popped up to the paved path by McNally High School, we saw the first course marshall, my friend Chris. I told him to call the race directors immediately and let them know they shouldn’t send the 30k racers over those trails, that they were way to wet. I don’t really know what happened to that message, but I do know I repeated it to a few more course marshals and the volunteers at the first aid station in Gold Bar park. The aid station reassured me that the rest of the course was re routed and we wouldn’t be on trails we shouldn’t be on. Except that we dove right back into single track, destroying some of the most beloved mountain bike trails in the city. The course doubled back on itself when we turned to head west, and soon we started seeing the 30k racers coming towards us. While it was fun to see so many familiar faces, the devastation continued as we slid, scrambled, destroyed vegetation just so we could stay upright, and moved a whole lot of clay as it stuck to our shoes and legs. It was an absolute mud fest. I passed Conor as he trudged through the trails, pulling flagging. I found out later they did decide to send the 30k racers back on wide trails, so I assume that’s what he was doing. I could see he was upset about how bad the situation was too. I held my tongue. He didn’t need my opinion. He already knew. This was a disaster.

As I came back to the start finish line before heading out on the second half of the course to the west of Emily Murphy, I asked one of the race directors (Sarah) if there was anymore single track on that half of the course. She said yes, there was some. My heart dropped. I should have stopped. But I didn’t. Sunk cost.

They did eventually reroute the 50k racers off of Selkirk Knights trail, but only after the lead pack had already passed. They responded, but too little too late.

Afterwards Sarah told me she never imagined the consequences of inaction would be so severe. But isn’t that true, that sometimes paralysis in the face of having to make a decision can be catastrophic? It’s easy to look back in hindsight and see all the things you should’ve done, but in the moment all you see is a million what ifs and a desperate urgency to have something work out the way you planned. I get it. As a race director you obsess over every detail and think through every possibility to ensure the day runs smoothly. The thought of having to pivot to conditions has massive consequences, and there’s always the fear that you’ll make the wrong decision.

I finished strong, happy to be done and able to change into something dry, and splurge on the incredible post race tacos, doughnuts, coffee and finisher beer. But I didn’t feel good about anything that had happened out there. I immediately called my husband, an avid mountain biker, and felt I had to confess what I had just done.

The outrage from the mountain bike community was swift and indignant, and all over social media. I don’t blame them one bit. While some of them were rude, most of them, and many of us trail runners, were simply sickened at the destruction, left wondering what would happen next.

The NSU team remained silent online at first. I pictured them huddled down, crafting a careful response to the vitriol being cast their way.

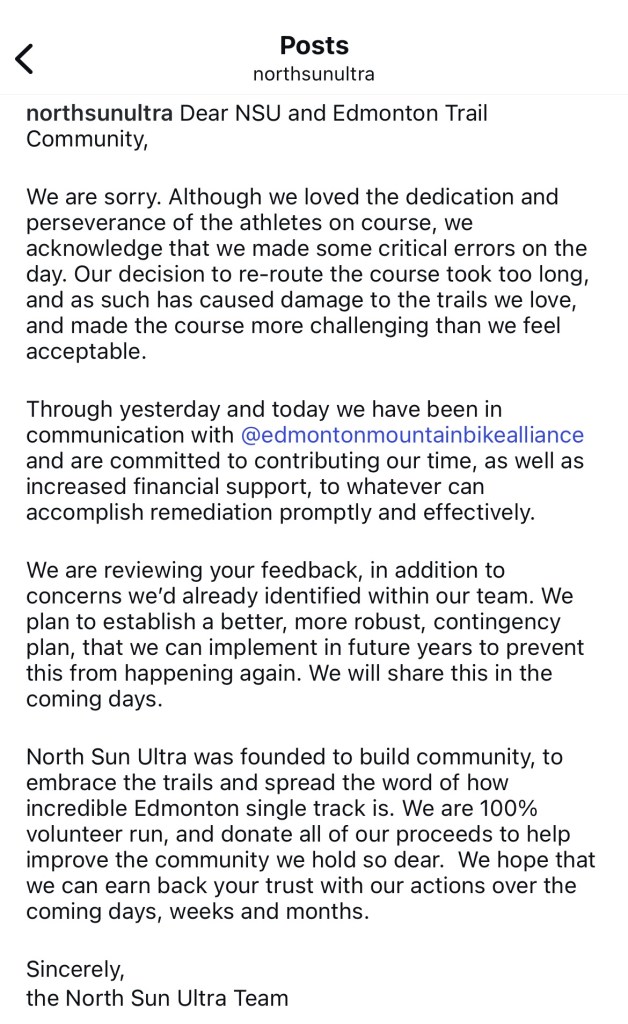

The post and email came the next day. An apology. Acknowledgment of the critical error in judgment. A promise to repair.

And what happened next was incredibly beautiful.

I often work with couples and parents in therapy on how to make an effective apology. The steps are

- Identify what you did wrong

- Acknowledge the impact it has on others

- Apologize sincerely

- Identify what you should have done differently

- Commit to repair and meaningful change for future behaviour

The North Sun team executed all those steps with grace, humility and integrity.

They owned up to making a mistake; they should have re routed or even cancelled the race, but they didn’t.

They validated the frustration from other trail users and didn’t sugar coat how much damage was done, even grieving that some damage is irreparable.

They said sorry, in lots of ways, to lots of people, including to us racers, even though we were the ones that ran through all that mud and are equally responsible.

They acknowledged the need for a better rain plan and better decision making protocol to protect trails.

And then they acted. Trail repair days and a generous donation to EMBA.

EMBA quickly organized three trail days and encourage NSU racers to sign up.

NSU race directors not only showed up to do the work, they encouraged the rest of the community to come out and do the work.

I went for one of the days, doing my best to smooth over trails, improve sight lines and drainage and learn how to do trail maintenance. We did our best to repair the trails, and most importantly the trust between trail use groups.

Trails are looking much better. And important lessons were learned about preventing damage in the future.

I’m so grateful to the NSU team for how they led with courage and integrity in the aftermath of the race. I know firsthand how difficult it is to put yourself out there to put on an event, and criticism is incredibly difficult to navigate. But my respect for the team, and this race has deepened.

And of course, so has my respect for the trails.